Picture California’s Central Valley — what do you see? If your mind immediately thought of an agricultural vista, such as the blooming almond trees, rows of crops, or cattle farms you might see driving down Interstate 5 or Highway 99, you’d be in good company. Looking out of your car window, it’s easy to let the landscape fool you into thinking this part of the state has always been farmland. Yet, California’s newest state park, Dos Rios, tells a different story — one of a continuously changing landscape and a purpose beyond the economic. Spend some time in this brand-new park, and you’ll see how much of the story of the Central Valley is still being written.

Dos Rios: An Overview

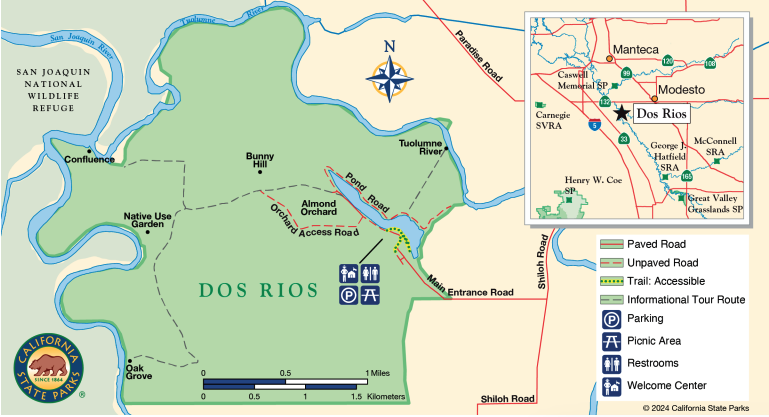

Located approximately eight miles west of Modesto, the approximately 1,600-acre Dos Rios park has much to boast about: it is California’s first new state park unit in nearly a decade, is the largest public-private floodplain restoration project in California history, and is heralded as the future of conservation in California. The park protects the confluence of the Tuolumne and San Joaquin Rivers, waterways that begin high in the Sierra Nevada Mountains and cross the state to provide drinking water to large portions of the San Francisco Bay Area.

Formerly a working ranch, the park now features guided hikes and newly built picnic tables and ramadas in this restored floodplain. This park illustrates that providing room for rivers to flood safely can provide recreational and educational opportunities in conjunction with restoration goals. Offerings and services at this park will continue to expand, building on decades of work that led to its creation.

Opening this park is an important milestone for California for many reasons. It helps the state come closer to achieving the 30x30 commitment, the goal that Governor Newsom set in October 2020 to conserve 30% of California’s land and coastal waters by 2030. It also ladders up to the state’s Outdoors for All initiative focused on expanding parks and outdoor spaces in communities that need them most, supporting programs to connect people who lack access and fostering a sense of belonging for all Californians in the outdoors. Notably, this park expands access to greenspace and recreational opportunities to Central Valley communities. “It’s a great addition to the state parks system in a part of the state that has less access to state parks,” says Rachel Norton, executive director of the California State Parks Foundation. “If you look at a map of California, you see tons of parks going up the coast. You see tons of parks in the Sierra Nevada and in the desert. There’s a lot along the edges. But in the center of the state, there’s just not a lot.”

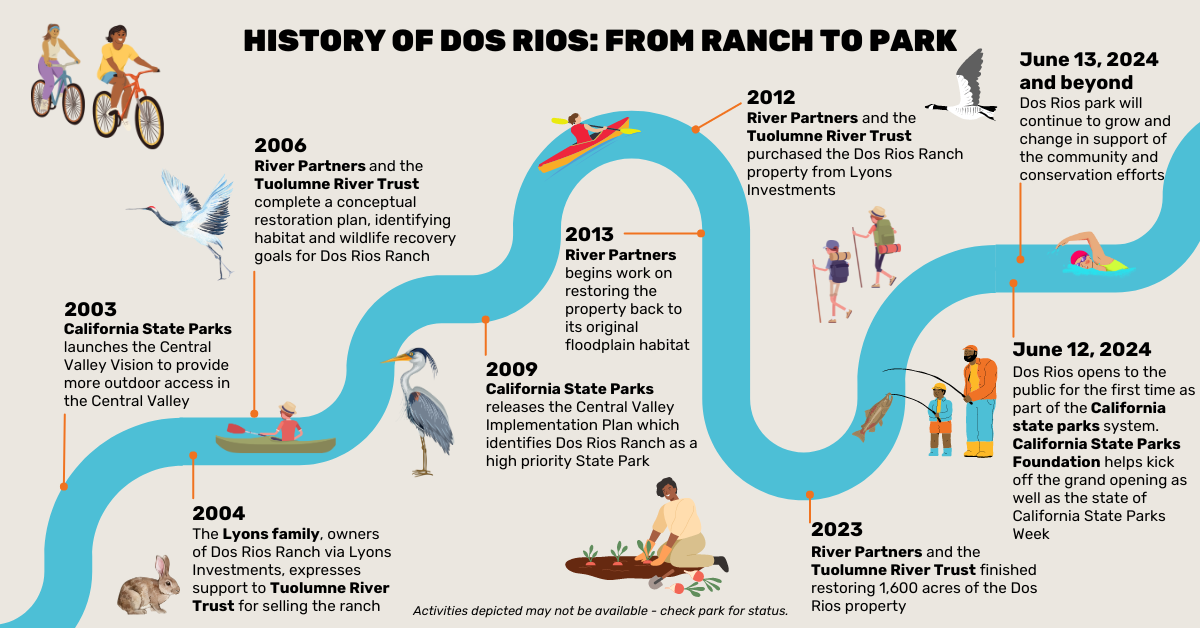

History: A Park Shaped by Partnership

The history of this land and the journey taken to make this park a reality showcases the interconnectness of conservation and recreation goals. Just as this land contains the confluence of two rivers, it has also long served as a place of connection for people and communities.

For many centuries, members of various Native nations would meet and gather on the land now contained by this park. In the 20th century, land records show that the property known as Dos Rios Ranch was first named Ranchos Dos Rios and was ultimately sold to Lyons Investment, the last private owners of the land, in 1987. In the early 2000s, River Partners and Tuolumne River Trust joined forces under a shared vision: transforming this farmland into native floodplain forests. These organizations secured over $40 million in funding from eleven different funding sources to make this vision a reality and led a decade-long effort to acquire and then transform this land. The scale of this effort is best exemplified by restoration work to plant over 350,000 native trees and other vegetation along the eight river miles of the San Joaquin River and Tuolumne River protected in this park.

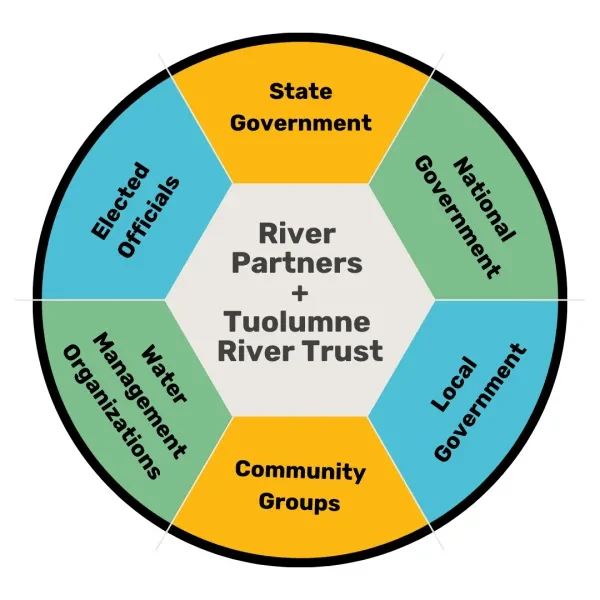

This work was not done alone. River Partners and the Tuolumne River Trust engaged over three dozen entities whose support and partnership were integral to preserving and protecting this land and ensuring that the park met the needs of the local community. In addition to getting buy-in and feedback from these groups, the collaborative process of creating this park ensured that the various goals and missions of partners worked in alignment instead of in competition.